“The U.S. economy is depression-proof.”

—Milton Friedman (1954)

Could another "Great Depression" occur—marked by a stock market crash, corporate profit collapse, and a rapid rise in unemployment to 25% or more? Most economists agree with Milton Friedman, who delivered a lecture on this topic in Sweden in 1954, asserting that today’s government leaders and central bank officials understand the fundamentals of economics and possess the technological tools to prevent a total collapse. He pointed to several institutional changes that made such a disaster unlikely: federal deposit insurance, the abandonment of the international gold standard, the expansion of government, increased social welfare spending, unemployment insurance, and other stabilizing mechanisms. Most importantly, the Federal Reserve knows how to avoid past mistakes and prevent a monetary meltdown—primarily through liquidity injections into markets and the banking system.

Indeed, Friedman’s prediction that another depression was unlikely has proven correct so far. We've gone through many periods of economic contraction and recession—even stock market crashes—but we’ve avoided another massive "Great Depression" akin to the catastrophe of the 1930s.

However, I’d like to emphasize that while another Great Depression may be improbable, it is certainly not impossible. We are depression-resistant—but not depression-proof. Before delving into explanations, let us first define the "Great Depression," why it occurred, why it lasted so long, and how we eventually emerged from it.

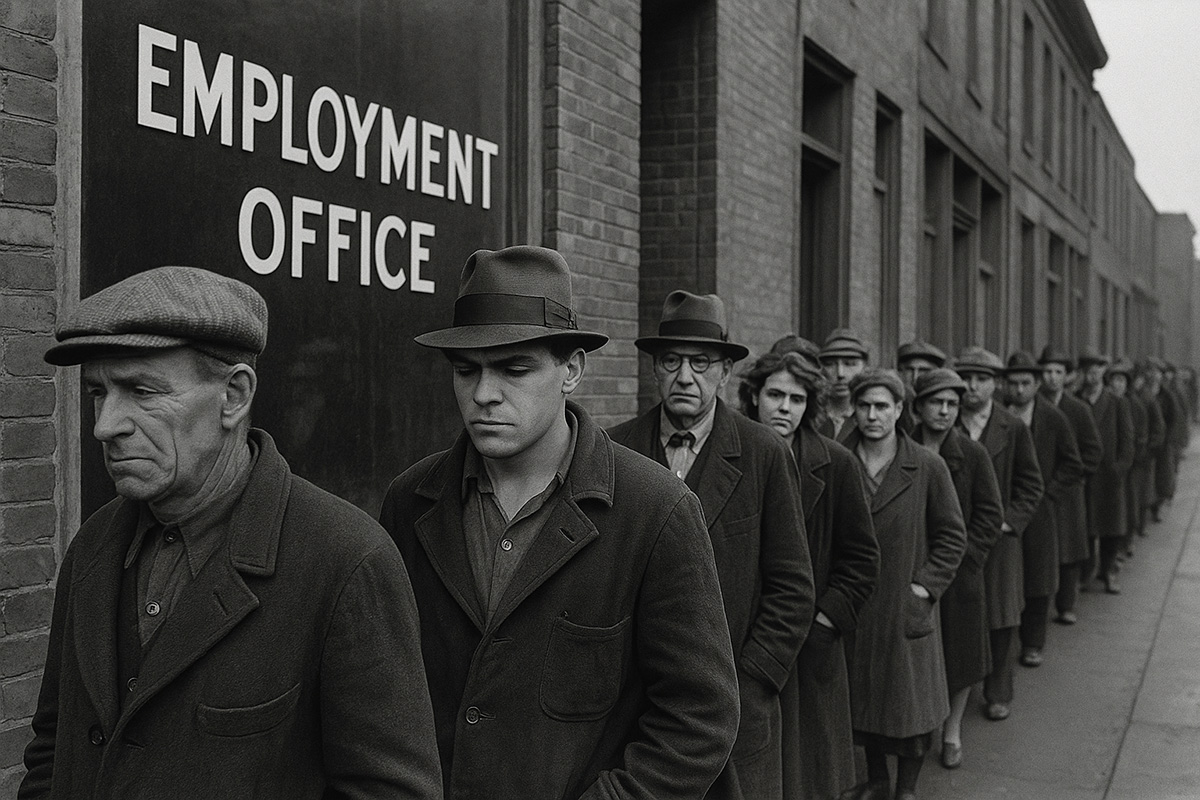

The Impact of the Great Depression

Although the long Great Depression of the 1930s may now seem a distant memory, its political and theoretical influence persists. The Depression created an environment that rejected economic freedom and laissez-faire policies, and instead fostered widespread support for government intervention throughout the Western world. It gave rise to the welfare state and an unwavering belief in “big government.” It drove most Anglo-American economists to doubt the old free-market doctrines and seek radical alternatives to capitalism, ultimately turning to the new Keynesian theory and demand-side economics.

Before the Depression, most Western economists embraced classical ideas—saving, limited government, balanced budgets, the gold standard, and Say’s Law. While many economists continued to support free markets and free trade at the micro level, they rejected traditional macroeconomic views after the war. They preferred consumption over saving, fiat currency over gold, deficit spending over balanced budgets, and active government intervention over limited authority. They accepted the Keynesian notion that free markets are inherently unstable and can lead to prolonged unemployment and idle resources. They blamed the Great Depression on unfettered capitalism and claimed that only massive government spending during World War II saved capitalism from collapse.

In short, the Great Depression opened the floodgates to collectivism in the United States and across the globe.

Fortunately, free-market economists gradually exposed the flaws in these arguments, and the tide slowly shifted back toward a re-establishment of traditional market economics. Three major questions had to be addressed:

What caused the Great Depression?

Why did it last so long?

Did World War II restore prosperity?

Economic historian Robert Higgs famously referred to these debates as “The Great Contraction,” “The Great Duration,” and “The Great Escape.”

The Cause of the Great Contraction

Many free-market economists tried to answer the first question, including Benjamin M. Anderson and Murray N. Rothbard. However, none had the impact of Milton Friedman’s empirical studies on money in the early 1960s. Friedman (with co-author Anna J. Schwartz) provided compelling evidence that it wasn’t the free market but government—specifically the Federal Reserve—that caused the Great Depression.

In one particularly arresting sentence, Friedman and Schwartz wrote:

"From the cyclical peak in August 1929 to the cyclical trough in March 1933, the stock of money fell by over one-third."

(This was shocking, as prior to Friedman’s work, the Fed did not publish monetary aggregates such as M1 or M2.)

Friedman and Schwartz also showed that the gold standard was not to blame, as some Keynesians had claimed. During the early 1930s, gold reserves actually increased, even as the Fed inexplicably raised the discount rate and allowed the money supply to contract and banks to collapse.

The Prolonged Downturn

Economic activity and employment stagnated throughout the 1930s, leading to a paradigm shift from classical economics to Keynesianism. Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, who opposed Keynes in the 1930s, became so disillusioned with the state of economic science that he abandoned it for political philosophy.

Why did the Depression last so long? Many free-market economists started where Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression left off—with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s assumption of power in 1933. Jane S. Shaw (Marquette University) applied Austrian insights to critique tax policy in the 1930s. I have summarized the causes of prolonged stagnation and unemployment, including the Smoot-Hawley tariff, tax increases, excessive government regulation, and pro-labor legislation.

More recently, Robert Higgs at the Independent Institute conducted a deep study of the 1930s, focusing on the lack of private investment. According to Higgs, private investment was discouraged by New Deal initiatives that destroyed business confidence—the very foundation of economic recovery. In short, the New Deal prolonged the Depression.

What Ended the Depression?

In another brilliant study, Higgs attacked the common myth that World War II saved the economy and restored full employment. War gave only the illusion of prosperity; in reality, private consumption and investment fell while Americans fought and died abroad. True prosperity—the genuine “Great Escape”—did not return until after the war, when wartime controls were lifted and military resources were redirected toward civilian production. Only then did private investment, consumer spending, and business confidence return to normal levels.

In summary, it was a long, hard struggle to restore belief in free-market capitalism. Thanks to the pioneering work of Friedman, Rothbard, Shaw, Higgs, and others, the intellectual battle has been largely won.

Could It Happen Again?

But what if government officials forget the lessons of the Great Depression? Here are some possible scenarios:

The government could destabilize the economy by making excessive promises on entitlements, welfare payments, and military spending—risking insolvency and runaway inflation.

It could trigger a permanent slump by overregulating, overtaxing, and expanding bureaucratic control over business.

A series of unexpected events could spark a major crisis—a run on the dollar, a real estate crash, sudden shifts from one asset class (e.g., government bonds) to another (e.g., gold or foreign currencies), a large-scale terrorist attack, or a natural disaster that overwhelms monetary authorities.

As long as the global financial system is built on an unstable inflationary policy, fragile fractional-reserve banking, open global markets, and unpredictable shocks, we cannot dismiss the possibility of chaos or economic catastrophe. Governments have long shown the ability to respond effectively to crises, and markets have recovered. But the most recent panic surely won’t be the last—and we must never underestimate the market’s capacity to react in unexpected ways.

Excerpted from the book: "EconoPower: How a New Generation of Economists is Transforming the World" by Mark Skousen. Published by Hindawi Foundation.

Comments