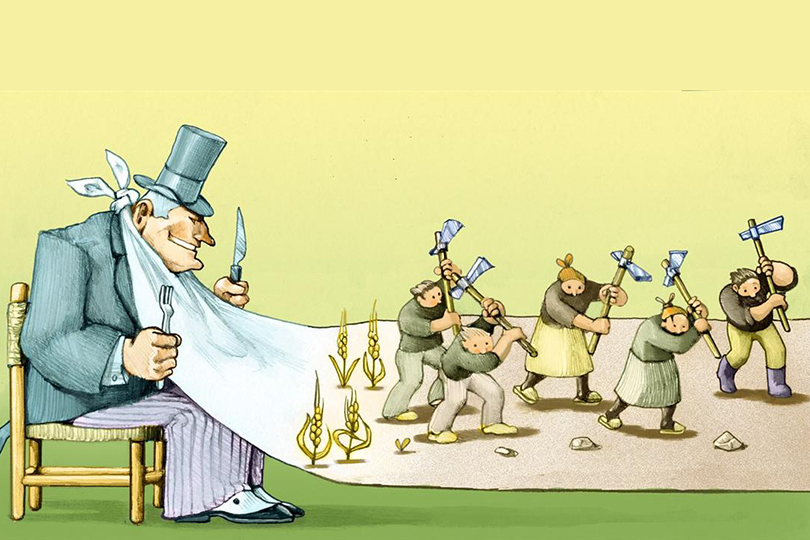

The end of the Cold War signaled the triumph of capitalism over other economic systems. But in the decades since, the modern form of American capitalism has started to show cracks. The incomes of the bottom 25% in the United States have not grown nearly as fast as those of the top 25%. In fact, the bottom 25% are no better off than they were 40 years ago—worse off, in some cases, than the poorest in other less robust free-market economies.

To placate low-income voters, politicians continue to modify the capitalist system to redistribute wealth to the poor. This has included progressive taxation, subsidies for healthcare and housing, food stamps, raising the minimum wage, and child tax credits. All of these measures aim to provide equal opportunity, but they also impede free markets, ultimately reducing the economic potential of the system.

It’s time to admit that our “one-size-fits-all” capitalist model does not fit everyone. We need to reform it—not by adding more patches or adopting a European-style welfare state, but through a two-track system: a free-market track for those who thrive in it, and another system for those who don’t.

The current 100% free-market model could be replaced with a 70-30 system, where about 70% of the workforce remains in the free market, and up to 30% receive a stable income.

This two-track system is similar to Universal Basic Income (UBI), but it differs in key ways. It is not universal and is offered only as an option to Americans who prefer financial security over the risks of the free market—and only to those who are working. The system would stabilize incomes and improve the well-being of low-income participants, while freeing up the rest of the economy to maximize growth and economic potential.

The fixed income would start at around $30,000 per year and increase to over $40,000 by retirement age. Workers on this income could be employed in either the public or private sector, but in both cases, the government would pay their wages. If they work for a private employer, the employer pays the government the market-rate wage, and the government pays the worker the fixed income—covering or benefiting from the difference.

At age 20, young Americans would choose between the free-market system and the stable-income system. Entry into either would be voluntary, based on personal preferences, while maintaining an approximate 70-30 workforce distribution. Before age 30, workers could switch between systems once. After 30, switching would still be possible but more costly. The stable income amount would be adjusted annually for new entrants to maintain the target participation rate of 25-30%.

Participants must be employed or actively seeking work to receive stable income payments.

Anyone can stay in the program and receive a fixed income for up to one year between jobs. After that, they would enter traditional welfare or disability programs. In this way, the program acts as a form of unemployment insurance—limited to one year. Those unable to work at all would remain covered by the current welfare and disability systems.

Non-dynamic modeling suggests the stable-income program would cost the government $800 billion in additional annual payments. But it would also save $265 billion by eliminating social assistance programs for those in the stable-income track, who would no longer receive unemployment insurance, food stamps, or child tax credits. Some benefits for free-market participants could also be reduced or removed.

For example, unemployment insurance could be extended to free-market participants earning up to $75,000 per year. However, they would not be eligible for food stamps or child tax credits. A safety net provision could allow those who fail in the free market to rejoin the stable-income program if they meet certain criteria.

Dynamic modeling would likely show greater reductions in government costs and increased revenue, thanks to removing constant efforts to make the free market “fairer.” Even without those additional benefits, $535 billion a year—or less than 2% of GDP—is a small price for a significant improvement in the well-being of 25-30% of Americans. Ideally, the justice dividend would yield benefits beyond economics, fostering a more stable political system where “pocketbook issues” are less divisive or high-stakes.

It’s time for a uniquely American adjustment to our outdated, “one-size-fits-all” capitalist system. Europe’s welfare states are 40 years ahead of the U.S. in trying to force more fairness into free markets—but it hasn’t worked. Per capita GDP in major European economies is 25% to 40% lower than in the U.S., and continues to fall. Adopting a two-track economy—preserving a strong free market for the majority and a stable income base for the minority—would continue to drive growth while limiting the destructive cultural and political effects of income inequality.

Source: Thomas C. Foley, former U.S. Ambassador to Ireland under President George W. Bush

https://www.newsweek.com/

Comments