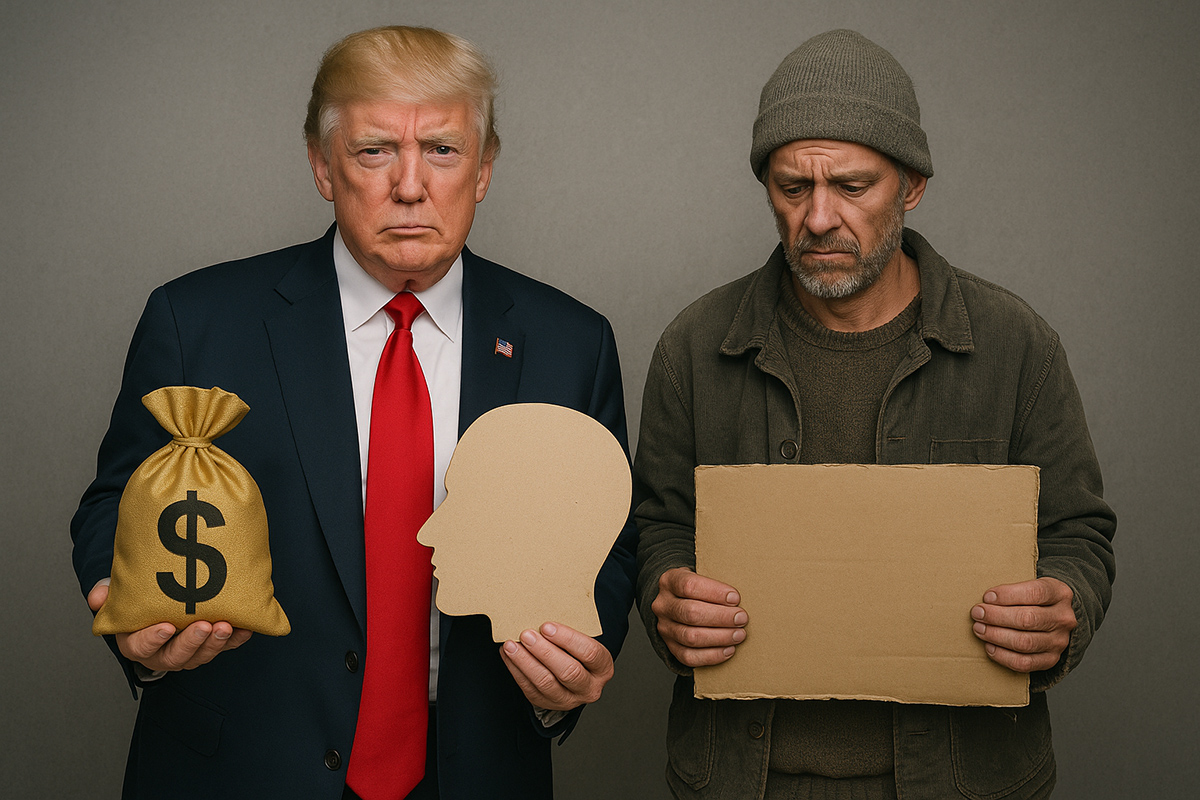

Donald Trump continued his walk along the pavement leading to Wall Street in New York City, only to suddenly stop in front of a beggar who was sitting on the ground, sifting through a lot of nothing—just a few coins and two dollar bills that covered those coins in an empty Coca-Cola cup.

Trump looked at the poor man with pity and said to him: “You, sir, own nothing, while I’m in debt for $900 million after losing my entire fortune. In the end, you’re richer than I am!”

The beggar replied with a smile: “I really am richer than you.”

But what if I got the money and then lost it? In that case, I would be considered a failure. I might even lose my health while trying to amass wealth. I wouldn’t know whether people liked me for who I am or for my money. And finally, I could get robbed—losing the wealth and my place to beg on the sidewalk of Wall Street, in the heart of New York, the city of wealth and financial speculation.

Trump left that beggar, quickening his pace to meet a friend who would help him recover his wealth again. But he kept repeating to himself that mainstream economic theory still uses expected utility models and rational factors in its analyses and testing.

Here, Trump paused again and thought to himself: Many of those analyses have failed to explain how wealth arises from economic booms or how that wealth is recreated. Still, he held onto the image of the “successful businessman,” which reflects skill in reputation management despite the pressures that pursued him.

In a world where the economy is accelerating and class disparities are increasing, human decisions are not measured solely by numbers, profits, or losses, but also by what is happening inside our brains. How does money—or the lack of it—affect our way of thinking?

Do the rich think differently than the poor, or does the environment and pressure alter the mechanisms of our brain function itself?

This is the realm of neuroeconomics, which merges economics, psychology, and neuroscience. It now offers new tools to understand the labyrinths of class-based thinking, where decisions are not merely rational choices but outcomes of complex neural interactions—fraught with fear, hope, stress, and sometimes deprivation.

In this journey, we dive deep into the brain to understand how a poor person makes a financial decision under the pressure of need, and why the wealthy sometimes take risks without worry. We discover how money changes the way we see the world and how poverty reprograms the brain for survival instead of growth.

Perhaps Donald Trump was unaware of the emergence of neuroeconomics, a behavioral science formed from a blend of neuroscience and economics, as we mentioned. This field tries to find commonalities in behavior regarding utility maximization and neural response metrics, all of which focus on the brain’s role in blood flow. The brain truly consists of multiple sections and systems that all engage in guiding decision-making.

Many decisions are made under risky conditions, leading human tendencies either toward risk-taking to maximize utility or toward risk aversion by sacrificing some benefits.

Studies and research in the United States have revealed many exceptional and anomalous behaviors, as well as common patterns that no longer align with the principle of utility maximization—including the risk aversion displayed by the Wall Street beggar sitting on the pavement when he encountered Donald Trump, the gambler who had become bankrupt.

Trump went through major financial and commercial losses before becoming President of the United States—experiences often cited as examples of volatility in the world of money and high-risk decisions, and sometimes even used to study economic behavior from a neuroeconomic perspective. Those bankruptcies were the result of risky investment decisions in the casino and real estate sectors.

Trump is considered a model of high-risk, high-reward decision-making.

He may have a neural tendency toward risk-taking and an ability to ignore the fear of failure—traits associated with relatively low activity in brain regions linked to fear or caution, such as the amygdala.

Thus, neuroeconomics reveals that various regions in the brain differ in their sensitivity to risk assessment or uncertainty in human behavior related to economic decision-making, depending on the shape, structure, and nature of the prefrontal cortex of the human brain.

While the poor focus on the probability of loss—no matter how small—the rich focus on the probability of gain—no matter how small as well. Each group looks at the same glass half-filled with water: the poor believe they must know everything in advance and have access to information for every reaction, which is rarely feasible due to high costs; meanwhile, only the rich possess the information portfolios necessary for making utility-maximizing decisions, and these are exclusively within their reach and neural networks, helping them increase their wealth—regardless of their brain cortex composition, as neuroeconomics promises.

While traditional economics assumes individuals are rational and always act to maximize their utility, neuroeconomics shows that decision-making is not always rational. It is influenced by emotion, intuition, biases, and neural activity.

In conclusion, neuroeconomics is, as we noted, an interdisciplinary field combining economics, neuroscience, and cognitive psychology to understand how individuals make economic decisions.

It studies the neural and mental processes behind economic behavior, such as decision-making, risk, reward, and personal preferences. This requires decision-makers in free markets to design effective marketing campaigns based on an understanding of how the brain responds to advertising and propaganda. It also calls for the development of policies that account for people's cognitive biases, as well as the enhancement of negotiation or investment strategies based on a deeper understanding of decision-making mechanisms.

It is an economically complex world—full of conflict, thought, and inequality—in the making or looting of wealth…!

Comments